- Home

- Heather Muzik

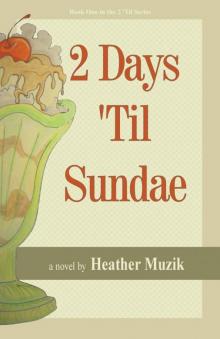

2 Days 'Til Sundae (2 'Til Series Book 1) Page 3

2 Days 'Til Sundae (2 'Til Series Book 1) Read online

Page 3

“The question of giants,” Catherine mumbled, sucking on her finger.

“So what’s your prob man?” Georgia sounded a bit tipsy.

“I just got a paper cut on this damn box.”

“Oh poor baby.”

Catherine could hear her brand of snide sympathy. “Suck this,” she said, holding up her middle finger, the same one she just so happened to have sliced.

Georgia was from Michigan, daughter of parents who have never been to the Peach State in their lives. Then again, the beauty was in the irony. What made it even better was the fact that she was a pale (very pale) redhead with faint freckles who would be risking life and limb if she lived in the south. Her long legs were milky white with pink undertones and dotted here and there with more freckles—a constant source of frustration for her, but Catherine would take them in a heartbeat over her own shorter, tanner, stubbier variety. Georgia was all straight angles where Catherine was curves, and all waves where Catherine was straight. They were an awkward pair that would have made a good comedy team: Georgia—tall and lean, with red and golden curls and life in her hair; Catherine—short and “voluptuous,” with brown (often stringy) hair. She was pretty much all shades of brown—hair, eyes, and skin (at least in the summer). Right now, though, her skin was pale with golden undertones, and translucent enough to show the finest veining where it pulled taut—which was the case in most places, at least for now. She and Georgia were night and day, and as such they had never competed for a man in their lives—the recipe for a successful female friendship.

Their whole opposite thing went right down to this very minute and second in time, where Georgia was a happily married woman while Catherine, as her friend put it, was as free as the ocean breeze and the eagle’s wing and all those poetic things that just mean alone. Georgia had tied the knot just before she turned thirty, a deadline Catherine had also been shooting for, but considering her birthday was only five days later than her friend’s and she’d gone stag to Georgia’s wedding…. To add insult to injury, her friend’s name was now Georgia Love, wife of Mr. Thomas Love. It was so aristocratic… and perfect… and sickening. Of course Catherine was just the teeniest bit jealous. Her friend was a kept woman now. When she married, she quit working—permanently. She said it was preparation for all the kids they were going to have, but so far that part hadn’t worked out quite as expected.

When the bleeding stopped, Catherine went back to work in the box. Something had rattled in there when she picked it up to toss it into the corner with the other empties. It was trapped under the flap of cardboard that had just filleted her finger. She lifted the flap carefully and fished underneath, her fingers clasping upon a ring. She pulled it out and stared at it in disbelief. It was a tiny ring with a butterfly that was enamel-painted in orange and green and blue. Truly hideous, and yet the most precious piece of jewelry she had ever owned. It was her first real piece of jewelry, a gift for her fifth birthday. It had moved from finger to finger as she slowly outgrew it, and she remembered being heartbroken when, in fifth grade, Jeanie Watts made fun of how childish it was, pointing out her own ruby ring—her birthstone—that her godmother had given her like she was Cinderella or something. That was when Catherine had given it to Josey, who wore it all the time. She had always figured that her sister must have been wearing it when she—

Suddenly Catherine felt a little woozy. She looked at her almost full wine glass. She hadn’t thought of Josephine in an embarrassingly long time, and the memories hit her with unexpected force. There was a time when she would have thought it impossible not to think about Josey, who was her every waking thought and most of her sleeping ones for so long after the funeral. She remembered that only a couple weeks before Josey died, her sister had lost the ring, and she’d been so angry with her. When Josey found it in her bed a few days later, Catherine had to fight the urge to reclaim it right then and there. And then Josey died and she’d been too afraid to think of where the ring ended up. That maybe it was buried underground. So it had gone forgotten—like Josey had been forgotten in Catherine’s rush to grow up and make her own way in the world, only to come up empty.

“What’s with you? You gonna be sick?” Georgia hiccupped. She was starting to sound like maybe she had gone past tipsy. “’Scuse me,” she said, and then burped loudly.

“That’s usually meant for after you burp,” Catherine said, shaking herself out of the cobwebs of the past.

“I was saying it for the hiccup.”

“Nobody excuses a hiccup. They just happen. It’s an inexcusable offense.”

“That would make it an offense that can’t be excused.”

“You know what I mean, Miss Literal.”

“That is Mrs. Literal to you,” Georgia chortled.

“Bitch!” It wasn’t snappy, but it was all she could conjure up on quick notice. She wondered if her advancing age had turned her own “Miss” label into “Ms.” now. Was that the way society tagged the unmarriable or past-date? Or was that just for the pre-owned?

“Catherine! Cat!”

“What?” she bellowed back. Her friends had always freely called her Cat because her mother’s reach wasn’t quite long enough.

“Whatcha gonna do with all the crap in the box? Get it? Like Jack in the—”

“Yeah, I get it,” she groaned.

Catherine shoved the little butterfly ring into her pocket and started putting her early life back into the boxes that Georgia had emptied in a tear, like a tornado hitting with full force and leaving nothing unturned, unencumbered by memories and lost moments. Now, without Elizabeth Hemmings’ supervision, it was going back in a jumble.

“I think I should maybe be an actress when I grow up,” Georgia said lazily.

“I think maybe you’ve had enough to drink,” Catherine admonished, turning to her friend who was busy twirling her feet in the air and swirling the wine in her glass.

“It’s not the wine. It’s all the blood that has rushed into my head.”

“You sure about that?”

“Well… maybe my tolerance is a little lower. We have been trying forever to get pregnant, so I cut back.”

Okay, so her friend’s life wasn’t perfect, but it was darn near close. Catherine hadn’t even been able to practice getting knocked up in pretty close to a year—serious dry spell.

“Why don’t you bring me those yearbooks.” Catherine pointed at the splayed selection of school years from the Trojans, an unfortunate name if ever there was one for a high school mascot. Condoms showed up at everything—pep rallies and graduations and school plays and honor society inductions. Enough prophylactics had mysteriously made their way onto school grounds that the school board had several times over the years voted to change the mascot. But that was the one thing that mobilized the otherwise apathetic student body, and en masse they would picket and strike and show up at meetings refusing to be called the Sloths or Kittens or whatever other inane name the old fogies came up with—though Beavers had a certain voting faction. The Chesterton Trojans had persevered and still remained, complete with the reservoir-tipped balloons that were batted around at football games.

“I have to say, you take a decent picture—ooh, except for ninth grade. Not a good year for you,” Georgia said soberly.

“Very funny.”

“I’m perfectly serious.”

“Well thanks for the unsolicited opinion. Why not help me put this stuff back now?”

“Are you keeping everything?”

“No. I just don’t feel like doing this anymore. I’ll get to it later,” Catherine said, still preoccupied by the emotional weight of her unexpected find. She didn’t want to share. Even though Georgia knew about Josey, she didn’t want to talk about it.

“Oh pooh. I thought this was great. I never knew this Catherine at all. I can’t believe that I missed all these great years.” She raked her hand through old ticket stubs from concerts and movies come and gone, more old report cards, pins, stickers,

friendship bracelets (the balance of the summer before sixth grade was spent on that fad). “And by the way, I love this look.” Georgia held the acid-washed jean jacket, festooned with band pins, up against her chest. “Obviously had a thing for hair bands, huh?” She flicked a Poison button nestled among Winger and Slaughter and Warrant and Trixter.

“Like you didn’t.”

“I didn’t leave any evidence, though. That’s the first rule of obsessions: never get caught.”

“I’ll remember that for the future,” Catherine said with chagrin.

“And you had a pot problem?” Georgia asked in shock, holding the jacket away from herself and wrinkling her nose.”

Catherine snatched the jacket from her friend’s clutches and held it protectively against herself. “I wasn’t smoking it! I was standing two rows in front of the guys who were!”

“Is that what you told your mom?”

“It’s the truth! And I didn’t have to tell my mother anything. Elizabeth Hemmings has never smelled pot before in her life. She wouldn’t have a clue what it was.”

“Cat, seriously, what are you going to do with this stuff?” Georgia asked, already onto other things. “Space is at a premium here. You’ve already got too many tenants in your closet.” She motioned toward the bedroom where the closet door was cracked open and clothes were bursting out of the gap.

“I could paint the boxes and make them into furniture.”

-4-

Catherine woke out of a sound sleep, her chest tight with panic and her ears perked for clues as to what had startled her. She couldn’t find the vestiges of a dream in the shadows of her mind or anything out of the ordinary in the apartment around her. The faucet was dripping in the bathroom like always. The red glow from the Sal’s Pizza sign outside her window was present as usual, like a siren call for cheesy goodness. The sound of a muffled television below calmed her some, reminding her that she was indeed not alone; exceptionally close neighbors were only a scream away if need be—separated by the thinnest barriers the building code allowed.

Her fingers found the tiny ring around her neck, worrying the metal band along the smooth chain, a gift from Pete Riggs that had come with a beautiful opal pendant—since removed. Pete was boyfriend number six if she counted the boys she “went out with” in middle school while actually never going anywhere and carefully disregarded the guys she had hooked up with now and then with no formal label between them. It was a true relationship, until that little gem of a gift came between them. Opal was most certainly not her birthstone as Pete seemed to think. It was Stacia King’s birthstone—the girl who had helped him with his college aps while Catherine, still only a junior, was down-and-out with mono (another sorry-ass gift from Pete).

After Georgia left the other night, Catherine had found the chain in her jewelry box and strung the butterfly ring onto it. Now she found her hand drawn to her neck, holding the ring like it was some sort of talisman. She listened to the faint reverberation from the friction between the band and chain as she slid the ring back and forth on its tether, hoping it would help bring sleep.

She was expected back at work in half a dozen hours, but her brain refused to be subdued. Every time she closed her eyes her lids would flap back open again, like a shade violently rolling up. She watched the minutes morph by in green on her clock. She tossed and turned until she was twisted into the sheets enough that it made her panic, reminding her of waking up on cold winter mornings mummified in her flannel nightgown. Resigned to her state of insomnia, she got up and trudged to the living room, flopped on the couch, and turned on the TV.

An old episode of Friends was the only light in the room, illuminating the space in a seemingly random pattern of intensity. Catherine glanced warily over at the boxes she and Georgia had pushed into the corner of the living room to make room to dance around to Def Leppard like they used to last century. She didn’t know what she was afraid of. There was nothing really that shocking in them other than the fact that it was all a reminder that she had lost herself somewhere along the way.

She’d had so many plans back then—shifting and morphing easily with the capricious winds of adolescent angst. Even the hardest of knocks didn’t hurt for too long because it seemed like everything was before her. And by the time she was on the threshold of life as an adult, Catherine Marie Hemmings had been so certain she had it all figured out. She was going to marry Daniel Bell. She was going to have four children and a dog and a house in the suburbs. She had truly believed that by now she would be making regular pilgrimages back to the old hometown with her family in tow to visit the house she grew up in. The last sixteen years had steadily dismantled those dreams, beginning with her monumental dumping of Daniel Bell in front of everyone at Mercer’s Pub back in Chesterton during winter break of her freshman year, after she’d convinced herself that the new guys she happened to be meeting in college were better than anything her high school had produced. But she had self-corrected as needed and over the years it had become husband X and kids A and B who would be making that pilgrimage. Her plans might have been reduced to variables, and kids C and D had long since been taken off layaway, but until last weekend she’d still held out hope. And then the final fork in everything she had ever imagined—her parents were moving. The going home part was the one thing she thought would never change.

Life is real, not ideal, Catherine Marie.

Along with her dashed dreams, those boxes reminded her of how many other things had been lost over the years. Like her teddy bear bank filled with her most precious coins. It was just a stupid hollow plastic bear with a slice in its head and a stopper in its butt that was covered in (hopefully) fake fur. He had a red bowtie and a white sticker that said “I’m a Bank!” on the front, to dispel any ambiguities as to his purpose. Connor had won him for her at the Fireman’s Fair when he was eight. While he was riding rides and eating cotton candy and corn dogs, she was stuck at home with some kind of nasty bug that kept her running from her bedroom to the toilet all night. She had treasured that ridiculous bank, her consolation prize. She’d secured her financial future in that plastic fur-covered bear—filled it with buffalo nickels and half dollars and Susan B. Anthony dollars. It might have been a small collection, but it was important to her—not important enough to take with her when she went to college, or to come back for when she graduated and moved to New York, but important enough that it shouldn’t have been dismissed so gratuitously by her parents—I should never have taken the sticker off. She’d probably had enough coins in there to get a haircut at a real salon… better yet, a trim at the teaching college and an awesome new pair of jeans—there was always a ponytail for bad hair days but hiding body issues took a lot more ingenuity and dough.

Then it came to her—the rest of it. All of her toys and dolls were MIA. Like most girls since the dawn of the impossibly proportioned Barbie, she’d had plenty of those, but she’d also had an extensive collection of Strawberry Shortcake dolls—Angel Cake being her favorite. And there was her Cabbage Patch Kid, a little girl with short, blonde, looped-yarn hair and green eyes—the only one Santa had left at the North Pole that year, she was told, when bratty little Catherine said, “But I really wanted one with brown pigtails I can braid and brown eyes like mine.” She had saved all her dolls, boxing them up carefully when it finally became all too apparent that she could no longer keep them in her room where her friends might see she was still a baby who liked to play with toys. She hadn’t had the heart to give them away, not even to her own little sister. She’d asked her parents to store them away. And now they were gone, or at least overlooked in the attic or basement somewhere.

And what about Caramellie?

Caramellie was the one toy she hadn’t packed away all those years ago. Josey loved her almost as much as Catherine did. Deciding that Caramellie deserved better than a cardboard box, Catherine let her and her little sundae house live in Josey’s room so long as her sister promised not to lose any of the pieces and

to play with her carefully. And sometimes she would even play with Caramellie and Josey too, like a good big sister should.

Catherine’s heart skipped as her mind conjured up an image of Josey’s smiling face, the little doll with the bright orange hair cupped in her sister’s small hands. Caramellie couldn’t actually do much. She was all of about two inches tall, and her tiny body only had front to back hip joints and shoulder joints. Her head was huge in comparison—like a grape on top of a Tic Tac—and her weensy little feet could never hope to hold her upright. Catherine could picture the sundae house, molded plastic that looked like a tall green sundae cup with two scoops of caramel ice cream and caramel sauce, and then whipped cream and a cherry on top. It was so vivid. The house opened on a hinge at the bottom. The back laid out flat providing a molded backyard and pool. The three dimensional sundae stood on end, offering two floors of square footage for living space. The house was small, but it came furnished with a table, chair, bed, and a ladder to the first floor. Mattel made a good house. Catherine adored that little doll set. Letting Josey keep it was probably the nicest thing she’d ever done for her sister. And then Josey was taken away and the dollhouse disappeared—

What the heck does it matter?

She tried to tell herself it was just more junk she would have had to find a place for. That she didn’t have any daughter to pass it on to…. The fact that it was missing, along with all her other dolls, saved her trouble and closet space. But then there was that feeling still gnawing at the edges.

-5-

The house was decidedly un-spectacular. It was un-assuming and un-derstated. It was all things un- and yet it was the place she had crawled home to after every childhood humiliation, and the place she had skipped home to after every triumph. A severe colonial with no bells and whistles: straight classic lines, white clapboard siding, black shutters and front door. It probably looked standoffish to the casual passer by, but to her…. She was standing on the gray stone step where she’d had her first kiss—John Watts (she still felt her knees weaken slightly, even though she knew that now he was a priest of all things—that she never would have expected what with his lip prowess). She was poised to knock on the door that she had burst through when she got her acceptance letter into Penn State, the same excitement she had shown when Daniel Bell first asked her out and when she learned she was picked for safety patrol way back in elementary school. So many memories were tied to this place—something that terrified her when her sister died but with time it buoyed her by keeping Josey’s spirit alive. This was where her sister had been left behind as Catherine made her way in places that Josephine had never been and would never go.

2 Weeks 'Til Eve (2 'Til Series Book 3)

2 Weeks 'Til Eve (2 'Til Series Book 3) 2 Months 'Til Mrs. (2 'Til Series)

2 Months 'Til Mrs. (2 'Til Series) 2 Days 'Til Sundae (2 'Til Series Book 1)

2 Days 'Til Sundae (2 'Til Series Book 1)